Even more remarkably, the UW authors found that the re-development of orange-producing xanthophores requires thyroid hormone, the same hormone that turns tadpoles into frogs, suggesting that xanthophores undergo their own metamorphosis. At the same time thyroid hormone blocks development of the black cells, setting the proper shade overall.

"In the last 10 to 15 years people trying to understand these patterns have concentrated on how the three pigment cell types interact with each other. We showed the tremendous dependence on thyroid hormone for the pattern that develops," Parichy said.

Lead author is Sarah McMenamin, a postdoctoral fellow in Parichy's lab. Funding for the work was provided by the National Institutes of Health, which just awarded Parichy a new $1.25 million grant to study thyroid hormone signaling in pigmentation and melanoma.

Next in the Nature Communications paper, Parichy's group reports on a gene that drives the unusually early appearance of xanthophores – independent of thyroid hormone – in another species, the pearl danio. Unlike zebrafish this species lacks stripes: its pigment cells are intermingled and arranged uniformly on the body, giving it a pearly orange color.

By expressing this gene the same way in zebrafish, the researchers caused the fish to make extra-early xanthophores and the fish produced a uniform pattern like the pearl danio instead of their usual stripes.

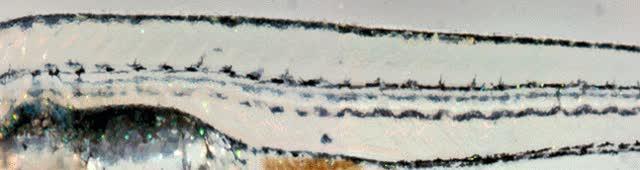

A 10-day-old zebrafish gets its stripes over the next 30 days, one image taken a day.

(Photo Credit: D Parichy Lab/U of Washington)

"Really simple changes in timing make totally different patterns," Parichy said.

This unexpected result shows that a core network of interacting cells can generate very different patterns in response to changes in timing, a discovery that could explain color pattern evolution across a variety of species. Lead author on the Nature Communications paper is postdoctoral scholar Larissa Patterson and the work was funded by the NIH.

"If you'd asked me five years ago if we're in a position to have some useful hypotheses about where patterns come from in other species, I'd have said, 'No,'" Parichy said. "But I think now we're really at the point where we understand a lot of the basics and we can start to frame testable hypotheses. We can see how much of this is just a simple difference in timing, a difference in thyroid hormone responsiveness or a difference in cellular communication itself."

Researchers have determined it's a certain gene that keeps pigment cells dispersed and gives the pearl danio its uniform orange color. By expressing this gene the same way in zebrafish, the zebrafish pigment cells also remained intermingled and the fish were essentially stripped of their stripes.

(Photo Credit: D Parichy Lab/U of Washington)

An adult zebrafish shows distinctive stripes.

(Photo Credit: D Parichy Lab/U of Washington)

Source: University of Washington