"Our results suggest that the bristle worm possesses independent, endogenous monthly and daily body clocks that interact," Tessmar-Raible says. "Taking this together with previous and other recent reports, evidence accumulates that such a multiple-clock situation might be the rule rather than the exception in the animal kingdom."

Kyriacou and colleagues used a combination of environmental and molecular manipulations of the daily clock to show that when the 24-hour circadian clock is disrupted in the sea louse, the 12.4-hour tidal clock keeps right on ticking.

"The surprise was to discover just how hard-wired, robust, and independent the tidal clock is in these animals; it keeps working no matter what we throw at its circadian clock," Kyriacou says.

This is a Eurydice crustacean swimming.

(Photo Credit: Zhang et al., Current Biology)

Similarly, Tessmar-Raible's team showed that bristle worms' moon-driven clocks, which provide the animals with an "intrinsic month," continued to function even when the researchers disrupted the animals' circadian clocks. The two clock mechanisms do interact, however, as the researchers showed that the length and strength of the circadian rhythm are adjusted according to the circalunar clock.

"This means that there might be a whole level of regulation on the molecular and behavioral level for which we have just scratched the surface," Tessmar-Raible says.

These simultaneous discoveries in two marine species now raise new questions about the molecular and cellular natures of these separate clocks and their roles in animal behavior, the researchers say.

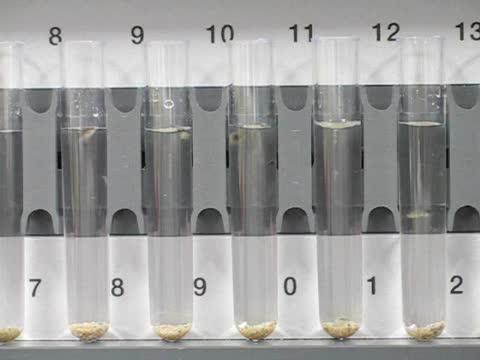

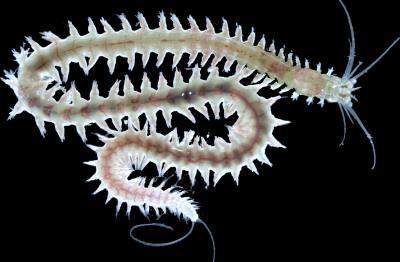

This is a premature adult Platynereis worm.

(Photo Credit: Zhang et al., Current Biology)

This is a premature adult Platynereis worm.

(Photo Credit: Zhang et al., Current Biology)

Source: Cell Press