While BECs are made from a dilute gas of atoms less dense than air, they have unusual collective properties, making them more like a fluid—or in this case, a superfluid. What does this mean? First discovered in liquid helium in 1937, this form of matter, under some conditions, can flow persistently, undeterred by friction. A consequence of this behavior is that the fluid flow or rotational velocity around the team's ring trap is quantized, meaning it can only spin at certain specific speeds. This is unlike a non-quantum (classical) system, where its rotation can vary continuously and the viscosity of the fluid plays a substantial role.

Because of the characteristic lack of viscosity in a superfluid, stirring this system induces drastically different behavior. Here, physicists stir the quantum fluid, yet the fluid does not speed up continuously. At a critical stir-rate the fluid jumps from having no rotation to rotating at a fixed velocity. The stable velocities are a multiple of a quantity that is determined by the trap size and the atomic mass.

This same laboratory has previously demonstrated persistent currents and this quantized velocity behavior in superfluid atomic gases. Now they have explored what happens when they try to stop the rotation, or reverse the system back to its initial velocity state. Without hysteresis, they could achieve this by reducing the stir-rate back below the critical value causing the rotation to cease. In fact, they observe that they have to go far below the critical stir-rate, and in some cases reverse the direction of stirring to see the fluid return to the lower quantum velocity state.

Controlling this hysteresis opens up new possibilities for building a practical atomtronic device. For instance, there are specialized superconducting electronic circuits that are precisely controlled by magnetic fields and in turn, small magnetic fields affect the behavior of the circuit itself. Thus, these devices, called SQuIDs (superconducting quantum interference devices), are used as magnetic field sensors. "Our current circuit is analogous to a specific kind of SQuID called an RF-SQuID", says Campbell. "In our atomtronic version of the SQuID, the focused laser beam induces rotation when the speed of the laser beam "spoon" hits a critical value. We can control where that transition occurs by varying the properties of the "spoon". Thus, the atomtronic circuit could be used as an inertial sensor."

This two-velocity state quantum system has the ingredients for making a qubit. However, this idea has some significant obstacles to overcome before it could be a viable choice. Atomtronics is a young technology and physicists are still trying to understand these systems and their potential. One current focus for Campbell's team includes exploring the properties and capabilities of the novel device by adding complexities such as a second ring.

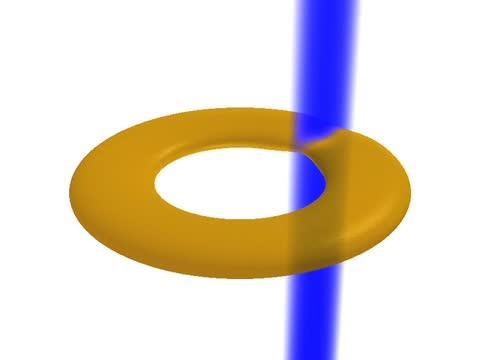

This is an animation showing a laser beam stirring a ring shaped quantum gas.

(Photo Credit: G. Campbell and authors on research paper)

This is the cover of Nature highlighting this research.

(Photo Credit: This cover was provided courtesy of Nature Press Office. Background image , Edwards/JQI)

Source: Joint Quantum Institute