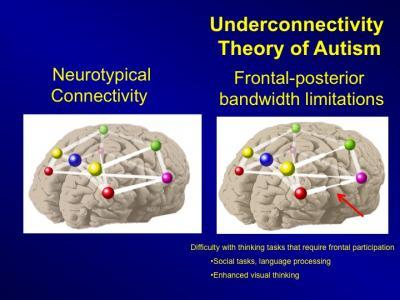

"The brain's processing of social information is performed by a network of areas, some of which are frontal, and some of which are posterior," Just explained. "Social impairments in autism are likely caused by the poor frontal-posterior connectivity. Similarly, language comprehension is performed by a network of frontal and posterior areas, and once again, poor connectivity may impair that network's functioning."

Just added, "This tells us where the problem lies in autism. We can now focus on designing therapies that attempt to either improve the white matter — something we have already proven is possible through behavioral interventions — or help the brain develop work-around strategies."

In a groundbreaking study published in 2009, Just and his colleagues showed for the first time that compromised white matter in children with reading difficulties could be repaired with extensive behavioral therapy. Their imaging study showed that the brain locations that had been abnormal prior to the remedial training improved to normal levels after the training, and the reading performance in individual children improved by an amount that corresponded to the amount of white matter change.

"This new research and model makes way for modifying people's brains and possibly helping people with autism. It also points at the likely source of autism," Just said.

In addition to autism, these findings also have implications for a number of other psychiatric illnesses that involve white matter deficiencies, such as schizophrenia and Alzheimer's disease, providing a way to relate the anatomical deficiencies to thought processes.

Autism has long been a scientific enigma, mainly due to its diverse and seemingly unrelated symptoms -- from social and communication disorders to restricted interests -- and their lack of correspondence to a particular biological ailment.

However, new research from Carnegie Mellon University's Marcel Just provides an explanation for some of autism's puzzles and gives scientists clear targets for developing intervention and treatment therapies.

Published in the journal "Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews," Just and his team used brain imaging and computer modeling to show how the brain's white matter tracts -- the cabling that connects separated brain areas -- are altered in autism and how these alterations can affect brain function and behavior. The deficiencies affect the tracts' bandwidth -- the speed and rate at which information can travel along the pathways.

Watch the full version of this video at http://youtu.be/eSR94zW8mrA.

(Photo Credit: Carnegie Mellon University)

Schematic diagrams of a normal brain (left) and an autistic brain (right) highlight the white matter alterations in autism.

(Photo Credit: Carnegie Mellon University)

Source: Carnegie Mellon University