This work confirms and extends landmark research published by Dr. Blaser's lab in 2012 in Nature. That research showed that mice on a normal diet who were exposed to low doses of antibiotics throughout life, similar to what occurs in commercial livestock, packed on 10 to 15 percent more fat than untreated mice and had a markedly altered metabolism in their liver.

Among the unanswered questions in that study was whether the metabolic changes were the result of altered bacteria or antibiotic exposure. This latest study addresses the question by transferring bacterial populations from penicillin-exposed mice to specially bred germ-free, antibiotic-free mice, starting at three weeks of age, which corresponds to infancy just after weaning. The researchers discovered that mice inoculated with bacteria from the antibiotic-treated donors were indeed fatter than the germ-free mice inoculated with bacteria from untreated donors. "This shows us that the altered microbes are driving the obesity effects, not the antibiotics," says Dr. Cox.

Contrary to a longstanding hypothesis within the agricultural world that holds that antibiotics reduce total microbial numbers in the gut, therefore reducing competition for food and allowing the host organism to grow fatter, the team found that the penicillin did not, in fact, diminish bacterial abundance. It did, however, temporarily suppress four distinct organisms early in life during the critical window of microbial colonization: Lactobacillus, Allobaculum, Candidatus Arthromitus, and an unnamed member of the Rikenellaceae family, which may have important metabolic and immunological interactions. "We're excited about this because not only do we want to understand why obesity is occurring, but we also want to develop solutions," says Dr. Cox. "This gives us four potential new candidates that might be promising probiotic organisms. We might be able to give back these organisms after antibiotic treatments."

The researchers worked with six different mouse models over five years to obtain their results. To identify bacteria, they used a powerful molecular method that involves extracting DNA and sequencing a subunit of genetic material called 16S ribosomal DNA. Altogether, the scientists evaluated 1,007 intestinal samples, which yielded more than 6 million sequences of bacterial ribosomal genes, the order of the nucleotides that spell out DNA. Studies like these are possible because of technological advances in high-throughput sequencing, which allows scientists to survey microbes in the gut and other parts of the body. The Genome Technology Center at NYU Langone Medical Center played a key role in identifying the genetic sequences in the study.

Martin Blaser, M.D., and Laura Cox, Ph.D., discuss their work on early antibiotic exposure in mice.

(Photo Credit: NYU Langone Medical Center)

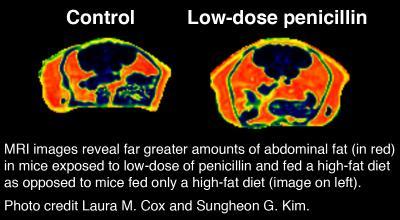

These MRI images reveal far greater amounts of abdominal fat (in red) in mice exposed to low doses of penicillin and fed a high-fat diet as opposed to mice fed only a high-fat diet (image on left)

(Photo Credit: Laura Cox and Sungheon G. Kim,NYU Langone Medical Center/Blaser Lab)

Source: NYU Langone Medical Center / New York University School of Medicine