"When we looked at seizure (sei) we noticed that there is another gene on the opposite strand of the double-stranded DNA molecule called pickpocket 29 (ppk29)," Ben-Shahar said. This was interesting because seizure codes for a protein "gate" that lets potassium ions out of the neuron and pickpocket 29 codes for a gate that lets sodium ions into the neuron.

Neurons are "excitable" cells, he said, because they tightly control the gradients of potassium and sodium across their cell membranes. Rapid changes in these gradients cause a nerve to "fire," to stop firing, and to repolarize, so that it can fire again.

The scientists soon showed that transcription of these genes is coordinated. When the flies are too hot, they make more transcripts of the sei gene and fewer of ppk29. And when the flies cooled down, the opposite happened. If the central dogma held in this case, the neurons might be buffering the effects of heat by altering the expression of these genes.

One problem with this idea, though, is that gene transcription is slow and the flies, remember, seize in seconds. Was this mechanism fast enough to keep up with sudden changes in the environment?

Does RNA interference regulate gene expression?

But the scientists had also noticed that the two genes overlapped a bit at their tips. The tips, called the 3' UTRs (untranslated regions), don't code for protein but are transcribed into mRNA.

That got them thinking. When the two genes were transcribed into mRNA, the two ends would complement one another like the hooks and loops of a Velcro fastener. Like the hooks and loops, they would want to stick together, forming a short section of double-stranded mRNA. And double-stranded mRNA, they knew, activates biochemical machinery that degrades any mRNA molecules with the same genetic sequence.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0H6EgLCYcX4&feature=youtu.be

Double-stranded RNA binds to a protein complex called Dicer that cuts it into fragments. Another protein complex, RISC, binds these fragments. One of the RNA strands is eliminated but the other remains bound to the RISC complex. RISC and its attached RNA then becomes a heat-seeking missile that finds and destroys other copies of the same RNA. If the mRNA molecules disappear, their corresponding proteins are never made.

It turned out that heat sensitivity in the fly is all about potassium channel, said Ben-Shahar. What if, he thought, the two mRNAs stuck together, the mRNA segment encoding the potassium channel was bound to RISC and other copies of the potassium channel mRNA were destroyed. This was another, potentially faster way the neurons might be controlling the excitability of their membranes.

A designer fly provides an answer

Which is it? Is regulation occurring at the gene level or the mRNA level?

To find out, the scientists made designer fruit flies that had various combinations of the genes and their sticky noncoding ends. One of these transgenic fly lines was missing the part of the gene coding for the ppk29 protein but still made lots of mRNA copies of the sticky bit at the end of ppk29. When there were lots of these isolated sticky bits, sei mRNA levels dropped. This fly was as heat sensitive as a fly completely missing the sei gene.

This combination of genotype and phenotype held the answer to the regulatory problem. First of all, mRNA from one gene (ppk29) is regulating the mRNA of another gene (sei). And, second, the regulatory part of ppk29 is the untranslated bit at the end of the mRNA. When this bit sticks to a complete transcript of the sei gene (including, of course, its sticky bit), the RISC machinery destroys any copies of the sei mRNA it finds.

So the gene that codes for a sodium channel regulates the expression of the potassium channel gene. And it does so after the genes are transcribed into mRNA; it's mRNA-dependent regulation.

The interaction between sei and ppk29 is unlikely to be unique, Ben-Shahar said. The potassium channel is highly conserved among species, and analyses of the genome sequences in flies and in people show that two of three fly genes for this type of potassium channel and three of eight human genes for these channels have overlapping 3' UTR ends, just as do sei and ppk29.

Why does this regulatory mechanism exist? Ben-Shahar hates getting out in front of his data, but he points out that transcribing DNA into mRNA is a slower process than translating mRNA into protein. So it may be, he said, that neurons maintain a pool of mRNAs in readiness, and mRNA interference is a way to quickly knock down that pool to prevent the extra mRNA from being translated into proteins that might get the organism in trouble.

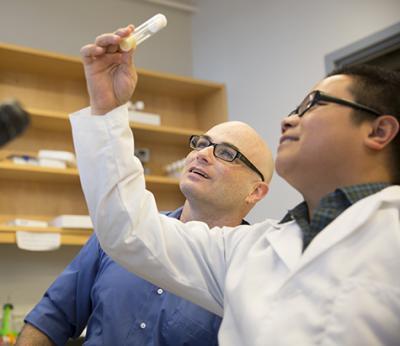

Ben-Shahar describes research with fruit flies that shows messenger RNA plays an active as well as a passive role in the cell. In addition to encoding for a protein, it can mark other mRNAs for destruction, preventing them from making the proteins they code for.

(Photo Credit: Yehuda Ben-Shahar, Susanne DiSalvo, James Byard and Tom Malcowicz/WUSTL)

Yehuda Ben-Shahar, Ph.D., assistant professor of biology, (left) and Xingguo Zheng, a Ph.D. candidate in neuroscience and co-author on the paper, are examining fruit flies in the lab.

(Photo Credit: Whitney Curtis/WUSTL Photo Services)