But the paleontologists call for development of standard formats to help ensure data accessibility.

"Currently there is no single 3D format that is universally portable and accepted by all software manufacturers and researchers," the authors write.

Digitype is baseline for measuring future deterioration

SMU's digital model archives a fossil that is significant within the scientific world as a type specimen — one in which the original fossil description is used to identify future specimens. The fossil also has cultural importance in Texas. The track is a favorite from well-known fossil-rich Dinosaur Valley State Park, where the iconic footprint draws tourists, Adams said.

The footprint was left by a large three-toed, bipedal, meat-eating dinosaur, most likely the theropod Acrocanthosaurus. The dinosaur probably left the footprint as it walked the shoreline of an ancient shallow sea that once immersed Texas, Adams said. The track was described and named in 1935 as Eubrontes (?) glenrosensis. Tracks are named separately from the dinosaur thought to have made them, he explained.

"Since we can't say with absolute certainty they were made by a specific dinosaur, footprints are considered unique fossils and given their own scientific name," Adams said.

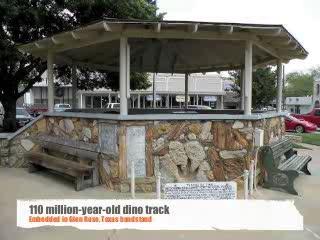

The fossilized footprint, preserved in limestone, was dug up in the 1930s from the bed of the Paluxy River in north central Texas about an hour's drive southwest of Dallas. In 1933 it was put on prominent permanent display in Glen Rose, Texas, embedded in the stone base of a community bandstand on the courthouse square.

The footprint already shows visible damage from erosion, and eventually it will be destroyed by gravity and exposure to the elements, Adams said. The 3D model provides a baseline from which to measure future deterioration, he said.

In comparing the 3D model to an original 1930s photograph made of the footprint, the researchers discovered that some surface areas have fractured and fallen away. By comparing the 3D model with a synthetically altered version, the researchers were able to calculate volume change, which in turn enables reconstruction of lost volume for restoration purposes.

Model comprises 52 scans totaling 2 gigabytes

Adams and his research colleagues took a portable scanner to the bandstand site to capture the 3D images. They employed a NextEngine HD Desktop 3D scanner and ScanStudio HD PRO software running on a standard Windows XP 32 laptop. The scanner and laptop were powered from outlets on the bandstand. The researchers used a tent to control lighting and maximize laser contrast.

Because of the footprint's size — about 2 feet by 1.4 feet (64 centimeters by 43 centimeters) — multiple overlapping images were required to capture the full footprint.

Raw scans were imported into Rapidform XOR2 Redesign to align and merge them into a single 3D model. The final 3D model was derived from 52 overlapping scans totaling 2 gigabytes, the authors said.

The full-resolution 3D digital model comprises more than 1 million poly-faces and more than 500,000 vertices with a resolution of 1.2 millimeters. It is stored in Wavefront format. In that format the model is about 145 megabytes. The model is free for downloading from a link on Palaeontologia Electronica's web site.

3D digital footprint also available as a Quick Time virtual object

A smaller facsimile is also available from the journal as a QuickTime Virtual Reality object. In that format, users can slide their mouse pointer over the 3D footprint image to drag it to a desired viewing angle, and zoom and pan.

Adams, a doctoral candidate in the Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences at SMU, describes the SMU researchers' protocol in a video at www.smuresearch.com, which also carries a link to the journal article and an image slideshow.

Besides the 3D model, included with the Palaeontologia Electronica article is a link to a pdf of the original 1935 scientific article in which SMU geology professor Ellis W. Shuler described and identified the dinosaur that made the track.

Shuler's article, no longer in print, is "Dinosaur Track Mounted in the Band Stand at Glen Rose, Texas," published in Field & Laboratory. The clay molds and plaster casts Shuler made of the bandstand track are now lost, Adams said.

Portable laser scanning technology allows researchers to tote a fossil discovery from field to lab in the form of digital data on a laptop. But standard formats to ensure data accessibility of these digitypes are needed, say paleontologists at Southern Methodist University, Dallas.

They field-scanned a 110 million-year-old Texas dinosaur track, then back at the lab created an exact 3D facsimile to scale. They share their findings -- and their downloadable 145-megabyte digital model -- in Palaeontologia Electronica.

The model duplicates a fossil that is slowly being destroyed by weathering because it's on permanent outdoor display, says SMU paleontologist Thomas L. Adams. He describes how the researchers created the digital model and discusses the implications for digital sharing and archiving. See the full video discussion at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2iNj0Pr9yR8&feature=player_embedded

(Photo Credit: Southern Methodist University)

Portable laser scanning technology allows researchers to tote a fossil discovery from field to lab in the form of digital data on a laptop. Paleontologists at Southern Methodist University, Dallas, field-scanned a Texas dinosaur track left by a large three-toed, bipedal, meat-eating dinosaur, most likely the theropod Acrocanthosaurus depicted in this Karen Carr illustration. Back at their lab, the researchers created an exact 3-D facsimile to scale. They share their findings -- and their downloadable 145-megabyte digital model -- in Palaeontologia Electronica.

(Photo Credit: Copyright Karen Carr and Karen Carr Studio Inc. See www.karencarr.com.)

Source: Southern Methodist University