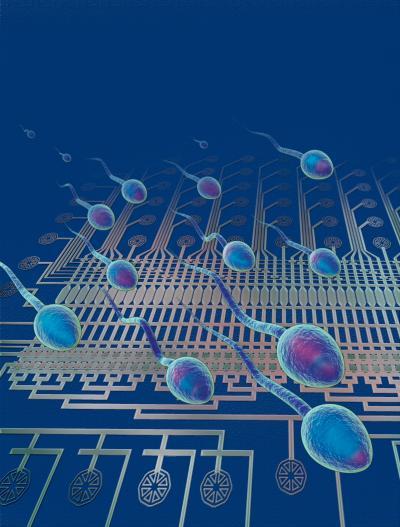

Every sperm cell looks essentially the same, with that characteristic tadpole appearance. But inside, sperm cells carry differences within their genes—even cells from the same man. Now, researchers provide a detailed picture of how the cell's DNA varies in a new study published in the July 20, 2012 issue of the Cell Press journal Cell. The techniques used could be helpful for understanding male reproductive disorders or, when applied to other areas of research, for characterizing normal and diseased cells in the body.

When parents pass on genetic material to their children through sperm and egg, the coded information found in their genomes is altered to increase genetic diversity and create unique features, a process that allows for natural selection and evolution. While this process has been characterized across human populations, scientists have had little information on how any particular individual's genes are changed in this way. "We have developed single-cell genome analysis technologies that enabled us to characterize how any given person mixes together their paternal and maternal inheritances to create potential offspring," says first author Jianbin Wang, a graduate student in the Department of Bioengineering at Stanford University.

Working under the guidance of Prof. Stephen Quake at Stanford University and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Wang and his colleagues obtained genome maps from 91 single sperm cells from one man, generating a personal map of the DNA within his sperm as well as a snapshot of the new mutations that occur within each sperm cell as its DNA is altered to increase genetic diversity.

Every sperm cell looks essentially the same, with that characteristic tadpole appearance. But inside, sperm cells carry differences within their genes -- even cells from the same man. Now, researchers provide a detailed picture of how the cell's DNA varies in a new study published in the July 20, 2012 issue of the Cell Press journal Cell. The techniques used could be helpful for understanding male reproductive disorders or, when applied to other areas of research, for characterizing normal and diseased cells in the body.

(Photo Credit: Layla Lang, layla@laylalang.com)

The technology goes beyond currently available maps of human populations to provide an individualized map for a single person—indeed, even a single cell.

"Application of this technology could significantly enhance our understanding of reproductive disorders. In addition, it may be paradigm shifting with respect to sperm or egg selection for in vitro fertilization," says coauthor Dr. Barry Behr of Stanford University. The authors note that their technology could have a variety of other clinical applications as well, such as characterizing differences in cancer cells taken from patients.

Source: Cell Press