Menlo Park, Calif. -- Researchers working at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have used the world's most powerful X-ray laser to create and probe a 2-million-degree piece of matter in a controlled way for the first time. This feat, reported today in Nature, takes scientists a significant step forward in understanding the most extreme matter found in the hearts of stars and giant planets, and could help experiments aimed at recreating the nuclear fusion process that powers the sun.

The experiments were carried out at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), whose rapid-fire laser pulses are a billion times brighter than those of any X-ray source before it. Scientists used those pulses to flash-heat a tiny piece of aluminum foil, creating what is known as "hot dense matter," and took the temperature of this solid plasma—about 2 million degrees Celsius. The whole process took less than a trillionth of a second.

"The LCLS X-ray laser is a truly remarkable machine," said Sam Vinko, a postdoctoral researcher at Oxford University and the paper's lead author. "Making extremely hot, dense matter is important scientifically if we are ultimately to understand the conditions that exist inside stars and at the center of giant planets within our own solar system and beyond."

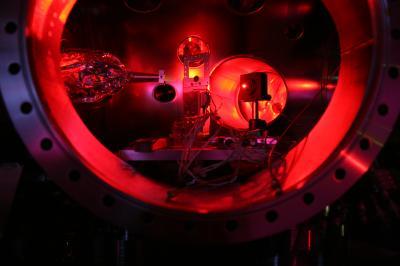

This photograph shows the interior of a Linac Coherent Light Source SXR experimental chamber, set up for an investigation to create and measure a form of extreme, 2-million-degree matter known as hot, dense matter. The central part of the frame contains the holder for the material that will be converted by the powerful LCLS laser into hot, dense matter. To the left is an XUV spectrometer and to the right is a small red laser set up for alignment and positioning.

(Photo Credit: University of Oxford / Sam Vinko)

Scientists have long been able to create plasma from gases and study it with conventional lasers, said co-author Bob Nagler of SLAC, an LCLS instrument scientist. But no tools were available for doing the same at solid densities that cannot be penetrated by conventional laser beams.

"The LCLS, with its ultra-short wavelengths of X-ray laser light, is the first that can penetrate a dense solid and create a uniform patch of plasma—in this case a cube one-thousandth of a centimeter on a side—and probe it at the same time," Nagler said.

The resulting measurements, he said, will feed back into theories and computer simulations of how hot, dense matter behaves. This could help scientists analyze and recreate the nuclear fusion process that powers the sun.

"Those 60 hours when we first aimed the LCLS at a solid were the most exciting 60 hours of my entire scientific career," said Justin Wark, leader of the Oxford group. "LCLS is really going to revolutionize the field, in my view."