Two overfeeding diets, carb and protein, both result in insulin resistance

Insulin, produced by the pancreas, is the hormone that tells our cells to absorb glucose, a necessary sugar molecule that provides our body, particularly the brain, with the energy to function, make repairs, move and grow.

In Type 2 diabetes, a person is insulin-resistant because his or her cells fail to respond to insulin's signal to absorb glucose. The disregulation of glucose upsets the body's delicate internal equilibrium, causing massive disruptions in normal cellular processes. These interruptions manifest in multiple disease symptoms, making Type 2 diabetes difficult to characterize, treat and cure.

To provide a good base model organism to study aspects of this complex disease, researchers in the Bauer lab wanted to determine whether flies develop diabetes-like metabolic changes when fed different diets. The researchers developed the insulin-resistant flies in two different ways: One group of fruit flies was overfed a carbohydrate-loaded diet; a second group of flies was overfed a protein-loaded diet. In both cases, the disruption had a profoundly detrimental effect on the flies' health and physiology.

SMU biologist Siti Nur Sarah Morris, lead author on the study, said the results the researchers observed were both expected and unexpected. The researchers expected the flies to gain weight, which they did. Carb-loaded flies gained excessive weight and got fat, just like humans who overeat sweets, french fries, pasta and ice cream. Protein-loaded flies also gained weight, but upon extreme overfeeding they lost weight, just like humans who follow the popular Atkins Diet, a weight loss program in which participants eat meat, seafood and eggs.

The researchers expected the carb-loaded fruit flies to develop insulin resistance, which they did.

In a surprising result, however, the fruit flies that overate protein also developed insulin resistance, but at a faster and more severe rate.

"Carb-loaded flies gain weight. Protein-loaded flies gain and then lose weight. So the two diets have exactly opposite effects on metabolism," Bauer said. "But too much of either one of them causes insulin resistance. That surprised us."

Overfed flies had shortened lifespans, differences in fertility

In other findings, carb-loaded flies experienced a profound decline in egg-laying, a measurement of fertility. In contrast, protein-loaded flies first experienced increased egg-laying, but the extreme diet led to decreased egg laying. Both diets led to shortened longevity, the scientists reported.

"The high-protein flies looked frail and unhealthy. They moved less, almost as if sedated," Morris said. "The fatter flies on the high-carb diet had massively decreased fertility; they flew less but still tried to move."

While both diets resulted in insulin resistance, differences were remarkable.

"The carb data imply a linear relationship between carb levels and health. The more carbs, the more weight, the more sugar storage and fat, the more insulin resistance and the less fertility," Bauer said. "But with protein, this relationship becomes parabolic, meaning all readouts go up, then come down again. The decreased storage we liken to a catabolic state that is primarily destructive for the body's optimum metabolic functioning, such as the ketosis typically seen in people eating Atkins-type diets."

Researchers at Southern Methodist University, Dallas, demonstrate that adult fruit flies fed either high-carb or high-protein diets develop metabolic abnormalities, including insulin resistance, which is a hallmark of Type 2 human diabetes.

For decades, fruit fly D. melanogaster has been used successfully to investigate multiple human diseases from Alzheimer's to cancer, but not diabetes. This new study demonstrates that diet profoundly influences fruit fly physiology and health and that insulin-resistant flies provide a new research tool for investigating the molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance. www.smuresearch.com. Higher resolution video at http://bit.ly/Ku2BO4.

(Photo Credit: SMUResearch.com)

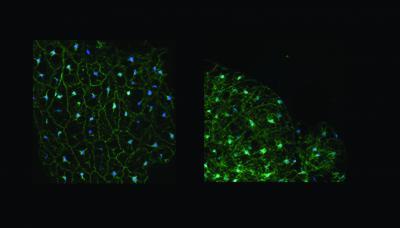

A dye test in fruit flies uncovers whether fat cells are responding to insulin. On the left, insulin signaling is active. On the right, insulin signaling is inactive.

The overfed fruit flies develop insulin resistance, making them a new tool for researchers to use in studying Type 2 human diabetes.

SMU researchers found that fruit flies overloading on carbs and protein not only gained weight but had shortened life spans -- and developed insulin resistance, a hallmark of Type 2 human diabetes.

The insulin-resistant fruit fly was developed in the lab of SMU biologist Johannes H. Bauer, principal investigator for the study. It was accomplished by feeding fruit flies a diet high in nutrients, said Bauer, an assistant professor in SMUs Department of Biological Sciences. That process mimics one of the ways insulin resistance develops in humans -- overeating to the point of obesity.

See http://bit.ly/Ku2BO4 for more images.

(Photo Credit: Image : Bauer, SMU)

Source: Southern Methodist University