"Astronomers have long suspected millisecond pulsars were spun up through the transfer and accumulation of matter from their companion stars, so we often refer to them as recycled pulsars," explained Anne Archibald, a postdoctoral researcher at the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON) in Dwingeloo who discovered J1023 in 2007.

During the initial mass-transfer stage, the system would qualify as a low-mass X-ray binary, with a slower-spinning neutron star emitting X-ray pulses as hot gas raced toward its surface. A billion years later, when the flow of matter comes to a halt, the system would be classified as a spun-up millisecond pulsar with radio emissions powered by a rapidly rotating magnetic field.

To better understand J1023's spin and orbital evolution, the system was regularly monitored in radio using the Lovell Telescope in the United Kingdom and the Westerbork Synthesis Radio Telescope in the Netherlands. These observations revealed that the pulsar's radio signal had turned off and prompted the search for an associated change in its gamma-ray properties.

A few months before this, astronomers found a much more distant system that flipped between radio and X-ray states in a matter of weeks. Located in M28, a globular star cluster about 19,000 light-years away, a pulsar known as PSR J1824-2452I underwent an X-ray outburst in March and April 2013. As the X-ray emission dimmed in early May, the pulsar's radio beam emerged.

While J1023 reached much higher energies and is considerably closer, both binaries are otherwise quite similar. What's happening, astronomers say, are the last sputtering throes of the spin-up process for these pulsars.

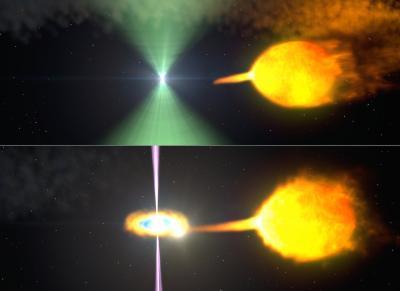

In J1023, the stars are close enough that a stream of gas flows from the sun-like star toward the pulsar. The pulsar's rapid rotation and intense magnetic field are responsible for both the radio beam and its powerful pulsar wind. When the radio beam is detectable, the pulsar wind holds back the companion's gas stream, preventing it from approaching too closely. But now and then the stream surges, pushing its way closer to the pulsar and establishing an accretion disk.

Gas in the disk becomes compressed and heated, reaching temperatures hot enough to emit X-rays. Next, material along the inner edge of the disk quickly loses orbital energy and descends toward the pulsar. When it falls to an altitude of about 50 miles (80 km), processes involved in creating the radio beam are either shut down or, more likely, obscured.

The inner edge of the disk probably fluctuates considerably at this altitude. Some of it may become accelerated outward at nearly the speed of light, forming dual particle jets firing in opposite directions -- a phenomenon more typically associated with accreting black holes. Shock waves within and along the periphery of these jets are a likely source of the bright gamma-ray emission detected by Fermi.

The findings were published in the July 20 edition of The Astrophysical Journal. The team reports that J1023 is the first example of a transient, compact, low-mass gamma-ray binary ever seen. The researchers anticipate that the system will serve as a unique laboratory for understanding how millisecond pulsars form and for studying the details of how accretion takes place on neutron stars.

"So far, Fermi has increased the number of known gamma-ray pulsars by about 20 times and doubled the number of millisecond pulsars within in our galaxy," said Julie McEnery, the project scientist for the mission at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "Fermi continues to be an amazing engine for pulsar discoveries."

Zoom into an artist's rendering of AY Sextantis, a binary star system whose pulsar switched from radio emissions to high-energy gamma rays in 2013. This transition likely means the pulsar's spin-up process is nearing its end.

Downloadable video: http://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/vis/a010000/a011600/a011609/.

(Photo Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center)

These artist's renderings show one model of pulsar J1023 before (top) and after (bottom) its radio beacon (green) vanished. Normally, the pulsar's wind staves off the companion's gas stream. When the stream surges, an accretion disk forms and gamma-ray particle jets (magenta) obscure the radio beam.

(Photo Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center)

Source: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center