Ancient Egyptian mummies revealed that humans have been hosting parasitic flatworms called schistosomes for more than 5,000 years. Today these parasites continue to plague millions of people across the world, causing roughly 250,000 deaths each year.

Researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign believe that one key to controlling this destructive parasite is being able to control their incredibly prolific life cycle that can produce tens to hundreds of thousands of schistosomes each generation.

In a recent study published in the journal eLife, they have come one step closer to understanding the unique mechanisms that allow larval schistosomes' germinal cells (stem cells that multiply and form other types of cells) to create thousands of clones inside a specific snail host.

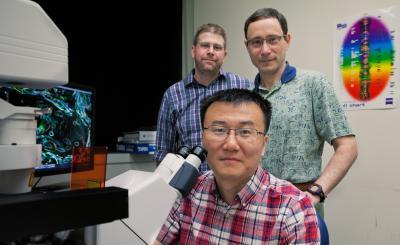

Institute for Genomic Biology Fellow Bo Wang (front), with Professor of Cell and Developmental Biology Phil Newmark (right) and postdoctoral researcher in Cell and Developmental Biology James Collins (left) from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign are studying the unique mechanisms that allow schistosomes' germinal cells to create thousands of clonal larvae that can then infect humans.

(Photo Credit: Photo by Kathryn Coulter, provided by Institute for Genomic Biology)

They discovered that germinal cells possess a molecular signature—a collection of expressed genes—that is similar to that of neoblasts (adult stem cells) that allow free-living, non-parasitic flatworms to regrow missing body parts. Among these genes, they identified some that are required for maintaining the germinal cell population.

This evidence suggests that schistosome larvae may have evolved by adapting a developmental program used by free-living flatworms in order to rapidly increase their population—essentially giving them the opportunity to reproduce twice within their life cycle, once asexually inside snail hosts and once sexually inside human hosts.

Illinois researchers believe they can apply this newfound developmental knowledge to future studies that may lead to ways to control, or even eradicate, schistosomes. They have already discovered that they can make the reproductive system of a planarian disappear by removing the function of a neuropeptide; eventually, they hope to do the same in schistosomes.

Source: Institute for Genomic Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign