"Cancer isn't one cell but it's an ecosystem, a community of cells," says Emerson. "This study begins the groundwork for potentially finding a way to understand and dial back cell diversity and adaptability during chemotherapy to decrease drug resistance."

To uncover how groups of cancer cells achieve functional diversity (through RNA) to survive chemotherapy, Lopez-Diaz dosed dishes of human pre-cancer and metastatic breast cancer cells with the cancer drug paclitaxel for a week and then removed the drug for a few weeks, mimicking the treatment cycle for a cancer patient. Surviving cells—usually one or two out of millions—began to repopulate but with subtle changes in their RNA, presumably enabling them to survive future doses of the cancer drug.

By pushing the boundaries of bioinformatics, a collaboration led by Mei-Chong Wendy Lee and Nader Pourmand at the University of California, Santa Cruz charted more than 80,000 pieces of RNA per new cancer cell—typically, single-cell studies by other approaches look at hundreds or so RNA pieces to distinguish fairly different cells from one another. This unusually thorough list helped the researchers tease out subtle differences between generations of same cancer cells treated with chemotherapy and chart how the cancer cell community increased diversity among its members through RNA.

"We found an overwhelming return to diversity after chemotherapy treatment that couldn't be explained by expected mechanisms," says Lopez-Diaz. "There is something else going on here, a 'philosopher's stone' to cancer cell diversity that we now know to look for."

In this video, a Salk researcher explains how cancer evolves to become drug resistant.

(Photo Credit: Salk Institute)

And when the team analyzed the gene expression profiles of the surviving cancer cell line, they were again surprised. "We thought they'd look like stressed cells with a few changes," says Emerson. "Instead, after a few population doublings they go back to the normal gene expression pattern and rapidly reacquired drug sensitivity." This adaptive behavior, Emerson speculates, lets the group of cancer cells prepare for the next unanticipated threat.

Another intriguing finding of the paper was that a high percentage of precancerous cells that underwent chemotherapy survived and proliferated, more so than either normal or cancerous cells. This led the pre-cancer cells to become more drug tolerant once they became a tumor. "The pre-cancer cells, when exposed to chemotherapy, evolved much faster and create a more drug-resistant state," says Lopez-Diaz. "This and other findings can now be explored into greater detail using the knowledge and perspective we have gained here."

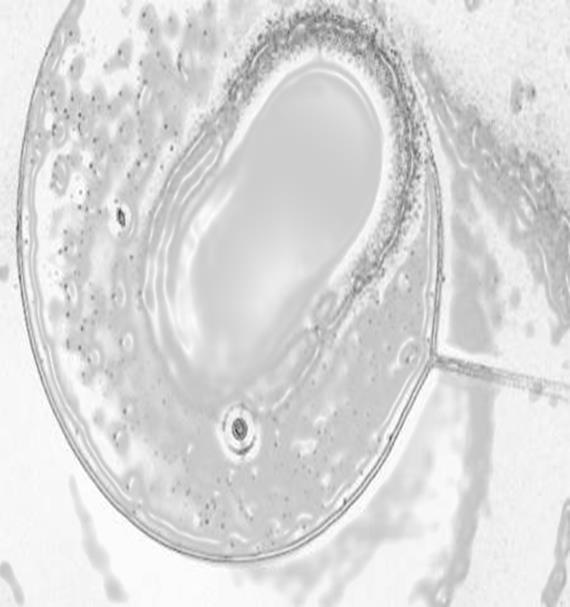

Researchers use a small pipette (right) to extract and analyze the RNA of individual breast cancer cells to track a cancer cell line's evolution.

(Photo Credit: Salk Institute)

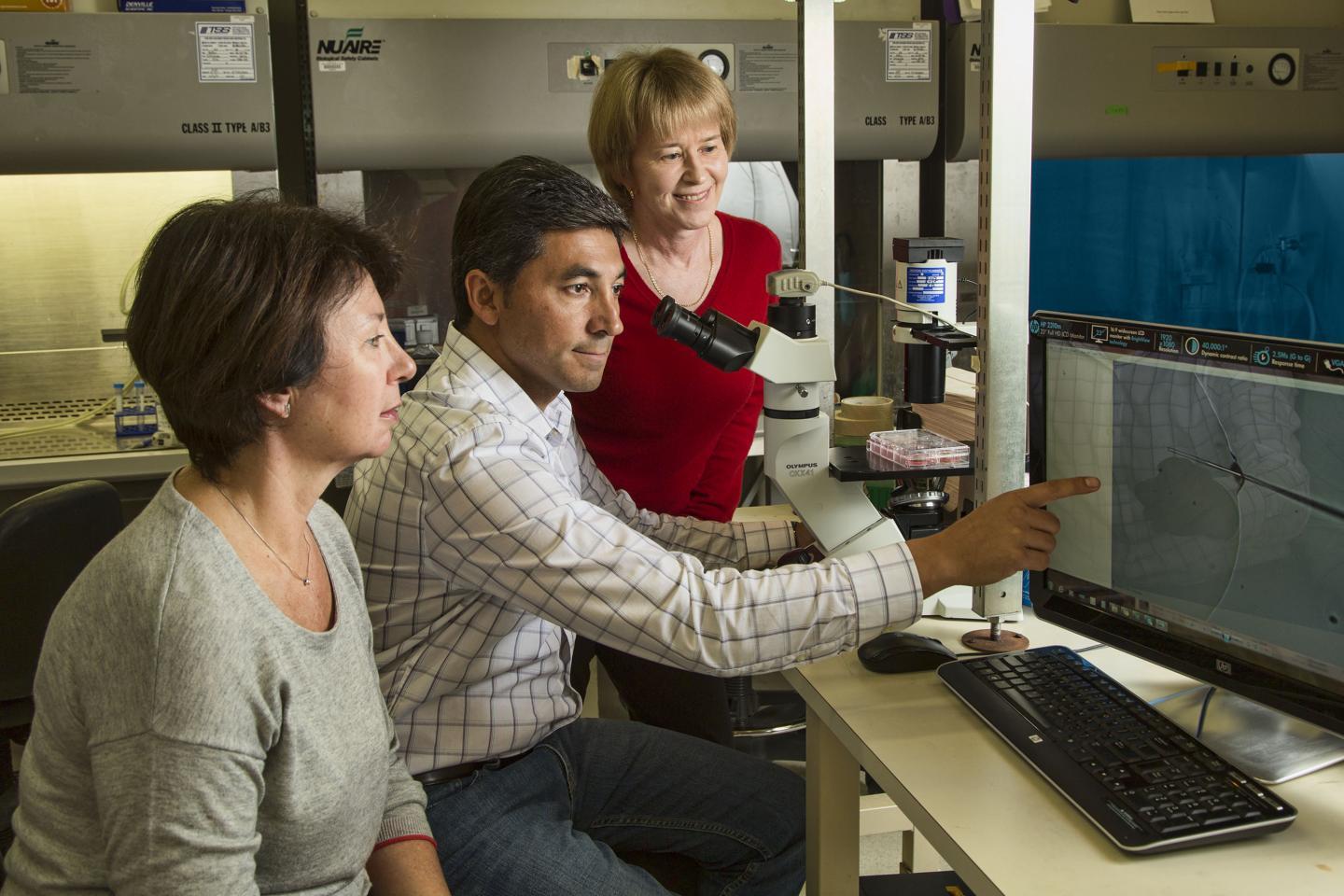

This image shows, from the left: Yelena Dayn, Fernando Lopez-Diaz, Beverly Emerson.

(Photo Credit: Salk Institute)

Source: Salk Institute