Remarkable anatomical changes

The fish showed significant anatomical and behavioural changes. The terrestrialized fish walked more effectively by placing their fins closer to their bodies, lifted their heads higher, and kept their fins from slipping as much as fish that were raised in water. "Anatomically, their pectoral skeleton changed to became more elongate with stronger attachments across their chest, possibly to increase support during walking, and a reduced contact with the skull to potentially allow greater head/neck motion," says Trina Du, a McGill Ph.D. student and study collaborator.

"Because many of the anatomical changes mirror the fossil record, we can hypothesize that the behavioural changes we see also reflect what may have occurred when fossil fish first walked with their fins on land", says Hans Larsson, Canada Research Chair in Macroevolution at McGill and an Associate Professor at the Redpath Museum.

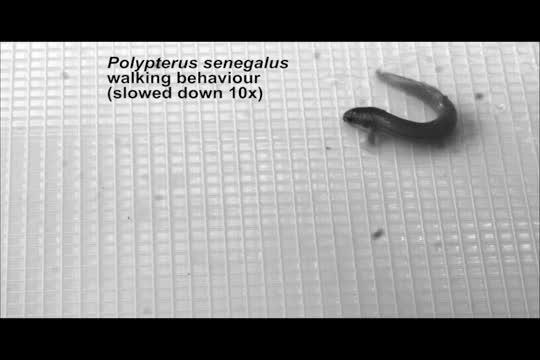

Polypterus senegalus walks across a sandy substrate. Fish use their fins and body in combination to move across a terrestrial substrate. Fins are planted one after the other to lift the head and anteriobody and the tail and body are used to push the fish forward over the planted fin.

(Photo Credit: E.M. Standen and T.Y. Du, H. Larsson)

Unique experiment

The terrestrialized Polypterus experiment is unique and provides new ideas for how fossil fishes may have used their fins in a terrestrial environment and what evolutionary processes were at play.

Larsson adds, "This is the first example we know of that demonstrates developmental plasticity may have facilitated a large-scale evolutionary transition, by first accessing new anatomies and behaviours that could later be genetically fixed by natural selection".

This is Polypterus senegalus.

(Photo Credit: A. Morin, E.M. Standen, T.Y. Du, H. Larsson)

This is Polypterus senegalus.

(Photo Credit: A. Morin, E.M. Standen, T.Y. Du, H. Larsson)

Source: McGill University