University of British Columbia and Vancouver Coastal Health scientistshave developed a potential cure for a rare eye disease, showing for the firsttime that a drug can repair a birth defect.

They formulated the drug Ataluren into eye drops, and found that it consistently restored normal vision in mice who had aniridia (ANN-uh-ridee-uh), a condition that severely limits the vision of about 5,000 people inNorth America. A small clinical trial with children and teens is expected tobegin next year in Vancouver, the U.S. and the U.K.

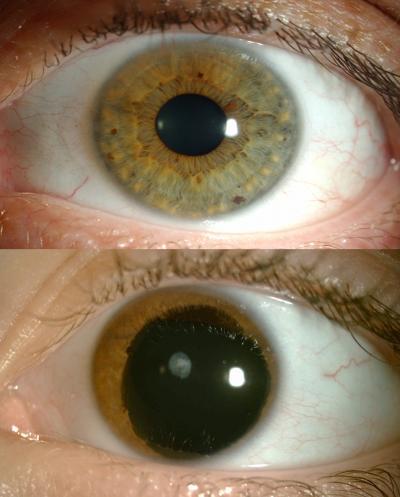

Aniridia is caused by the presence of a "nonsense mutation" – an extra "stopsign" on the gene that interrupts production of a protein crucial for eyedevelopment. Aniridia patients don't have an iris (the coloured ring aroundthe pupil), and suffer many other eye abnormalities.

Ataluren is believed to have the power to override the extra stop sign, thusallowing the protein to be made. The UBC-VCH scientists initially thoughtthe drug would work only in utero – giving it to a pregnant mother toprevent aniridia from ever arising in her fetus. But then they gave theirspecially formulated Ataluren eye drops, which they call START, to two-week-old mice with aniridia, and found that it actually reversed the damagethey had been born with.

Cheryl Gregory-Evans is an associate professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at University of British Columbia and neurbiologist at Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute.

(Photo Credit: Brian Kladko/UBC Faculty of Medicine)

"We were amazed to see how malleable the eye is after birth," said Cheryl Gregory-Evans, associate professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences and a neurobiologist at the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute. "This holds promise for treating other eye conditions caused by nonsense mutations, including some types of macular degeneration. And if it reverses damage in the eye, it raises the possibility of a cure for other congenital disorders. The challenge is getting it to the right place at the right time."

A video about the study is available at http://youtu.be/L9Gx1bUxCUg.

BACKGROUND | A POTENTIAL CURE FOR ANIRIDIA

Bad vision at birth, worse vision later: Aniridia is apparent at birth because of the missing iris. Toddlers with aniridia need eyeglasses to see, sunglasses or darkened contact lenses to protect their eyes from overexposure to light, and cannot read small text. Their eyes are continually moving, making it difficult for them to focus, and have higher internal pressure (glaucoma), which damages the optic nerve as they get older. They are also prone to corneal damage in their teens and early adulthood. Eventually, most people with aniridia are considered legally blind, and must resort to Braille or expensive electronic aids to read.

The plasticity of the eye: The reversal of tissue damage in young mice,published online today by the Journal of Clinical Investigation, fits with thefact that mammals' eyes aren't fully formed at birth. Human babies don'tdiscern colours until they are six months old, and their depth perceptionisn't fully developed until the age of five.

Nonsense suppressor: Ataluren, made by the New Jersey-based PTC Therapeutics, is thought to be a "nonsense suppressor" – it silences the extra "stop codon" on the gene and allows a complete protein to be assembled. The drug is currently being tested as a treatment for cystic fibrosis and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, which are also caused by nonsensemutations.

Top: a normal eye. Bottom: an aniridic eye.

(Photo Credit: UBC Faculty of Medicine)

A gritty solution: Gregory-Evans' first attempt at creating Ataluren eyedrops proved unsuccessful. The drug didn't dissolve, and thus irritated themice's eyes. So she turned to Kishor Wasan, a professor and associate deanin the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, who ground the drug into a very fine powder and combined it with a solution that adhered better to the eye.

A multidisciplinary team: Gregory-Evans also collaborated with herhusband, Kevin Gregory-Evans, the Julia Levy BC Leadership Chair inMacular Research and an ophthalmologist at the VCH Eye Care Centre, who treats B.C. patients with aniridia. He administered the vision tests for the mice used in the study.

Clinical trial: The forthcoming clinical trial, involving about 30 patients,will be led by Gregory-Evans in Vancouver, and is being supported by the Vision for Tomorrow Foundation, a U.S.-based charity focused on aniridiaand albinism (an absence of pigmentation in skin, hair and eyes that results in poor vision). If START is proven to be safe and effective, children with aniridia would use the drops twice a day for the rest of their lives. The drug would probably not reverse the condition in adults because their eyes would already be damaged beyond repair.

Cheryl Gregory-Evans is an associate professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at the University of British Columbia and neurobiologist at Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute.

(Photo Credit: Brian Kladko/UBC Faculty of Medicine)

Source: University of British Columbia