So-called "superheavy" elements owe their very existence exclusively to shell effects within the atomic nucleus. Without this stabilization they would disintegrate in a split second due to the strong repulsion between their many protons. The constituents of an atomic nucleus, the protons and neutrons, organize themselves in shells. Certain "magic" configurations with completely filled shells render the protons and neutrons to be more strongly bound together.

Enrique Minaya Ramirez and Michael Block are with the Shiptrap ion detector.

(Photo Credit: G. Otto / GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung)

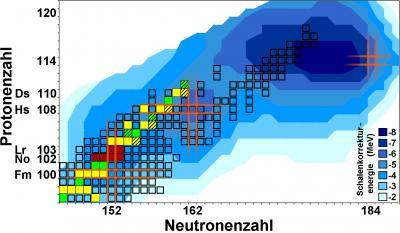

Long-standing theoretical predictions suggest that also in superheavy elements, filled proton and neutron shells will give rise to extraordinarily stable and hence long-lived nuclei: the "Island of stability". Still, after decades of research, its exact location on the chart of nuclei is a topic of intense discussions and no consensus has yet been reached. While some theoretical models predict a magic proton number to be at element 114, others prefer element 120 or even 126. Another burning question is whether nuclei situated on the island will live "only" hundreds or maybe thousands or even millions of years. Anyway, all presently known superheavy elements are short-lived and none have been found in nature yet.

Enrique Minaya Ramirez and Michael Block are at the SHIPTRAP setup at GSI.

(Photo Credit: G. Otto / GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung)

Precise information on the strength of shell effects that enhance binding energies of protons and neutrons for filled shells is a key ingredient for more accurate theoretical predictions. As the binding energy is directly related to the mass via Einstein's famous equation E=mc2, the weighing of nuclei provides access to the nuclear binding energies and thus the strength of the shell effects. With the ion-trap facility SHIPTRAP, presently the most precise balance for weighing the heaviest elements, a series of very heavy atomic nuclei in the region of the magic neutron number N=152 have now been weighed with utmost precision for the first time. The studies at hand focused on nobelium (element 102) and lawrencium (element 103). These elements do not exist in nature, so the scientists produced them at the GSI's particle accelerator facility and captured them in the SHIPTRAP. The measurements had to be performed with just a handful of atoms: for the isotope lawrencium-256 just about 50 could be studied during a measurement time of about 93 hours.

The new data will benchmark the best present models for the heaviest atomic nuclei and provide an important stepping stone to further refining the models. This will lead to more precise predictions on the location and extension of the "Island of stability" of superheavy elements.

This map shows presently known isotopes of the heaviest elements as squares. Blue: Calculated strength of shell effects. Red: nobelium and lawrencium isotopes studied. Green / yellow: Nuclides whose masses have been improved by the results. Orange: Location of closed shells.

(Photo Credit: Courtesy of Science/AAAS)