Astronomers have combined observations from the LABOCA camera on the ESO-operated 12-metre Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX) telescope [1] with measurements made with ESO's Very Large Telescope, NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, and others, to look at the way that bright, distant galaxies are gathered together in groups or clusters.

The more closely the galaxies are clustered, the more massive are their halos of dark matter — the invisible material that makes up the vast majority of a galaxy's mass. The new results are the most accurate clustering measurements ever made for this type of galaxy.

The galaxies are so distant that their light has taken around ten billion years to reach us, so we see them as they were about ten billion years ago [2]. In these snapshots from the early Universe, the galaxies are undergoing the most intense type of star formation activity known, called a starburst.

By measuring the masses of the dark matter halos around the galaxies, and using computer simulations to study how these halos grow over time, the astronomers found that these distant starburst galaxies from the early cosmos eventually become giant elliptical galaxies — the most massive galaxies in today's Universe.

"This is the first time that we've been able to show this clear link between the most energetic starbursting galaxies in the early Universe, and the most massive galaxies in the present day," explains Ryan Hickox (Dartmouth College, USA and Durham University, UK), the lead scientist of the team.

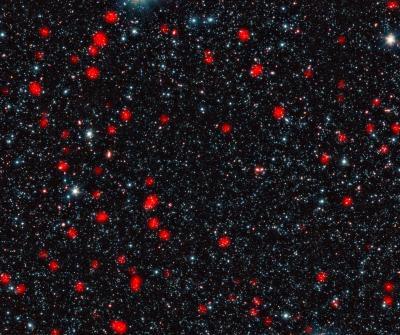

The LABOCA camera on the ESO-operated 12-meter Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX) telescope reveals distant galaxies undergoing the most intense type of star formation activity known, called a starburst. This image shows these distant galaxies, found in a region of sky known as the Extended Chandra Deep Field South, in the constellation of Fornax (The Furnace). The galaxies seen by LABOCA are shown in red, overlaid on an infrared view of the region as seen by the IRAC camera on the Spitzer Space Telescope.

By studying how some of these distant starburst galaxies are clustered together, astronomers have found that they eventually become so-called giant elliptical galaxies -- the most massive galaxies in today's universe.

The galaxies are so distant that their light has taken around ten billion years to reach us, so we see them as they were about ten billion years ago. Because of this extreme distance, the infrared light from dust grains heated by starlight is redshifted into longer wavelengths, and the dusty galaxies are therefore best observed in submillimeter wavelengths of light. The galaxies are thus known as submillimeter galaxies.

(Photo Credit: ESO, APEX (MPIfR/ESO/OSO), A. Weiss et al., NASA Spitzer Science Center)

Furthermore, the new observations indicate that the bright starbursts in these distant galaxies last for a mere 100 million years — a very short time in cosmological terms — yet in this brief time they are able to double the quantity of stars in the galaxies. The sudden end to this rapid growth is another episode in the history of galaxies that astronomers do not yet fully understand.

"We know that massive elliptical galaxies stopped producing stars rather suddenly a long time ago, and are now passive. And scientists are wondering what could possibly be powerful enough to shut down an entire galaxy's starburst," says Julie Wardlow (University of California at Irvine, USA and Durham University, UK), a member of the team.

The team's results provide a possible explanation: at that stage in the history of the cosmos, the starburst galaxies are clustered in a very similar way to quasars, indicating that they are found in the same dark matter halos. Quasars are among the most energetic objects in the Universe — galactic beacons that emit intense radiation, powered by a supermassive black hole at their centre.

There is mounting evidence to suggest the intense starburst also powers the quasar by feeding enormous quantities of material into the black hole. The quasar in turn emits powerful bursts of energy that are believed to blow away the galaxy's remaining gas — the raw material for new stars — and this effectively shuts down the star formation phase.

"In short, the galaxies' glory days of intense star formation also doom them by feeding the giant black hole at their centre, which then rapidly blows away or destroys the star-forming clouds," explains David Alexander (Durham University, UK), a member of the team.

Source: ESO