The human genome is far more complex than thought, with genes functioning in an unexpected fashion that scientists have wrongly assumed must indicate cancer, according to a new paper on what is called chimeric RNA – genetic material that results when genes on two different chromosomes produce "fusion" RNA in a way scientists say shouldn’t happen. Researchers have traditionally assumed these chimeric RNA are signs of cancer, of something gone wrong in the genetic transcription process.

But Hui Li, PhD, of the University of Virginia Department of Pathology shows that’s not always the case. Instead, these strange fusions can also be a normal, functional part of our genetic programming.

“This is actually a double-edged sword for cancer diagnosis and treatment. It basically says the old practice of finding any fusion RNA and claiming it’s a cancer fusion is over. We can’t just say, OK, we found a fusion, it must be a cancer marker, let’s translate it into a biomarker [to detect cancer],” Li said. “That’s actually dangerous. Because a lot of normal physiology also has fusion RNAs. There’s another layer of complexity.”

In the article, Li says chimeric RNA exists in normal physiology. “There’s a danger to assuming everything is cancer. That’s actually dangerous. Don’t rush to judgment about all of these chimera you find in cancer cells, because they could occur in normal cells.”

To build a foundation for discovery, Li is creating a database of naturally occurring fusions, to help sort normal chimeras from ones that might be signs of cancer. He doesn’t believe that any of the biomarkers now being used for cancer detection are problematic, but the database should accelerate the identification of new biomarkers by saving scientists from having to investigate each chimera individually.

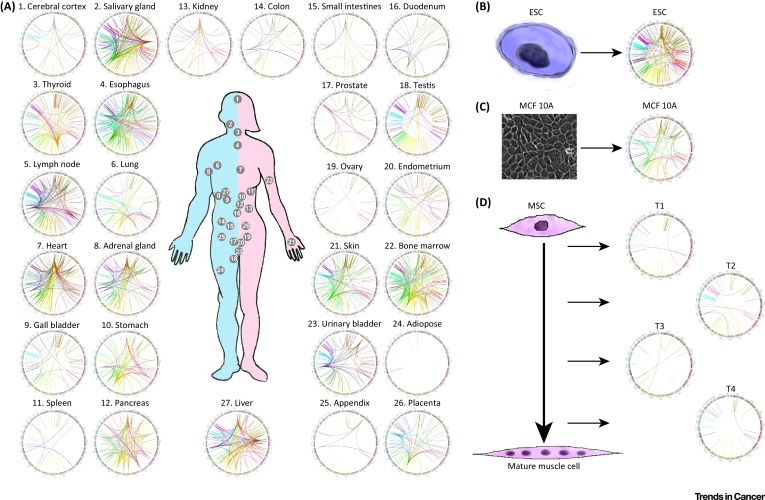

Chimeric RNAs in Normal Tissues and Cells. RNA-Seq data for (A) libraries covering 27 non-neoplastic human tissues, (B) human embryonic stem cells (ESC), (C) MCF10A breast epithelial cells, and (D) mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) collected at four differentiation steps (T1–T4) were analyzed using SoapFuse algorithmsii. Fusion events are shown by Circos plots; fused transcripts are illustrated by lines connecting two parental genes. Credit: DOI: 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.07.006

Chimeric RNAs in Normal Tissues and Cells. RNA-Seq data for (A) libraries covering 27 non-neoplastic human tissues, (B) human embryonic stem cells (ESC), (C) MCF10A breast epithelial cells, and (D) mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) collected at four differentiation steps (T1–T4) were analyzed using SoapFuse algorithmsii. Fusion events are shown by Circos plots; fused transcripts are illustrated by lines connecting two parental genes. Credit: DOI: 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.07.006

Because these natural chimeras were discovered so recently, relatively little is known about them. Li and his fellow researchers have shown that they occur when the instructions in our DNA are being carried out by RNA inside our cells. But the scientists can’t say how the fusions occur or why they occur or exactly how frequently they occur. And that speaks to how much there is to learn, Li noted. That knowledge will help us to better understand the human genome and to create better ways to detect – and hopefully defeat – cancer. “This opens a window for us to discover new biomarkers and new therapeutic targets, because there’s this whole other layer of complexity,” he said.