Researchers have developed a new technique that might one day be used to convert cells from heart disease patients into heart muscle cells that could act as a personalized treatment for their condition. The research is published online on August 22 in the journal of the International Society of Stem Cell Research, Stem Cell Reports, published by Cell Press.

The investigators previously reported the ability to convert scar-forming cells in the heart (called fibroblasts) into new, beating muscle in mice that had experienced heart attacks, thereby regenerating a heart from within. They accomplished this by injecting a combination of three genes into the animals' fibroblast cells. "This gene therapy approach resulted in new cardiac muscle cells that beat in synchrony with neighboring muscle cells and ultimately improved the pumping function of the heart," explains senior author Dr. Deepak Srivastava of the Gladstone Institutes and its affiliate, the University of California, San Francisco.

In this latest research, Dr. Srivastava and his colleagues coaxed fibroblasts from human fetal heart cells, embryonic stem cells, and newborn skin grown in the lab to become heart muscle cells using a slightly different combination of genes, representing an important step toward the use of this technology for regenerative medicine. Two other groups recently reported similar results using human fibroblasts.

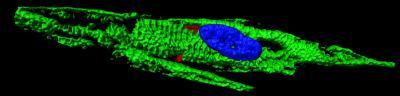

This is a 3D image of a reprogrammed human cardiomyocyte-like cell derived from a human fibroblast, stained with a marker of the sarcomere, the beating unit of a muscle cell.

(Photo Credit: Stem Cell Reports, Fu et al.)

The team envisions that introducing these genes into damaged hearts by gene therapy might convert fibroblasts into new muscle, thereby improving the function of the heart. "Over 50% of the cells in the human heart are fibroblasts, providing a vast pool of cells that could be harnessed to create new muscle," says Dr. Srivastava. However, additional research is needed to improve the process of reprogramming adult human cells in this way. Ultimately, replacing the genes with drug-like molecules that produce a similar effect would make the therapy safer and easier to deliver.

Source: Cell Press