Krumholz and UC Santa Cruz graduate student Yi Feng used supercomputers to simulate two streams of interstellar gas coming together to form a cloud that, over the course of a few million years, collapses under its own gravity to make a cluster of stars. Studies of interstellar gas show much greater variation in chemical abundances than is seen among stars within the same open star cluster. To represent this variation, the researchers added "tracer dyes" to the two gas streams in the simulations. The results showed extreme turbulence as the two streams came together, and this turbulence effectively mixed together the tracer dyes.

"We put red dye in one stream and blue dye in the other, and by the time the cloud started to collapse and form stars, everything was purple. The resulting stars were purple as well," Krumholz said. "This explains why stars that are born together wind up having the same abundances: as the cloud that forms them is assembled, it gets thoroughly mixed. This was actually a bit of a surprise. I didn't expect the turbulence to be as violent as it was, so I didn't expect the mixing to be as rapid or efficient. I thought we'd get some blue stars and some red stars, instead of getting all purple stars."

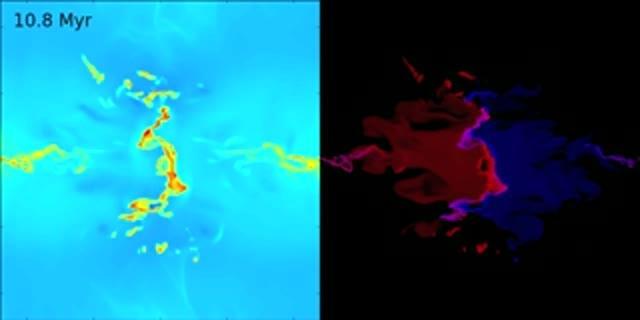

This computer simulation shows the collision of two streams of interstellar gas, leading to gravitational collapse of the gas and the formation of a star cluster at the center. The left side shows the density of interstellar gas (redder indicates higher density), and the right side shows the two "tracer dyes" added to show how the gas from the two streams mixes together during the collapse. Circles indicate stars.

(Photo Credit: Y. Feng and M. Krumholz)

The simulations also showed that the mixing happens very fast, before much of the gas has turned into stars. This is encouraging for the prospects of finding the sun's siblings, because the distinguishing characteristic of stellar families that don't stay together is that they probably disperse before much of their parent cloud has been converted to stars. If the mixing didn't happen quickly enough, then the chemical uniformity of star clusters would be the exception rather than the rule. Instead, the simulations indicate that even clouds that don't turn much of their gas into stars produce stars with nearly identical chemical signatures.

"The idea of finding the siblings of the sun through chemical tagging is not new, but no one had any idea if it would work," Krumholz said. "The underlying problem was that we didn't really know why stars in clusters are chemically homogeneous, and so we couldn't make any sensible predictions about what would happen in the environment where the Sun formed, which must have been quite different from the environments that give rise to long-lived star clusters. This study puts the idea on much firmer footing and will hopefully spur greater efforts toward making use of this technique."

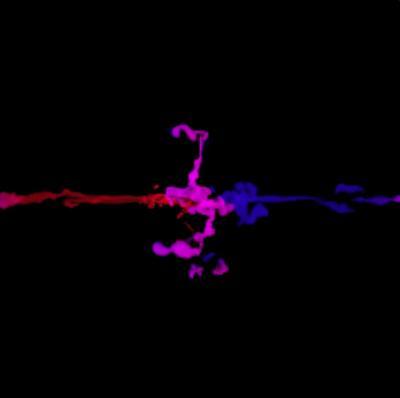

This is an image from a computer simulation shows a collision of two streams of interstellar gas, leading to gravitational collapse of the gas and the formation of a star cluster at the center. In this image, the gas streams were labeled with blue and red "tracer dyes," and the purple color indicates thorough mixing of the two gas streams during the collapse.

(Photo Credit: Y. Feng and M. Krumholz)

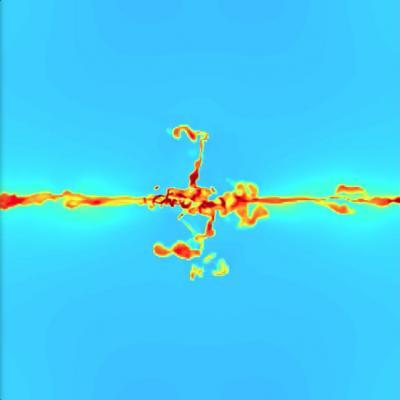

This is an image from a computer simulation shows a collision of two streams of interstellar gas, leading to gravitational collapse of the gas and the formation of a star cluster at the center. Colors represent the density of interstellar gas (redder indicates greater density).

(Photo Credit: Y. Feng and M. Krumholz)