"Dark matter in this mass range can be probed by direct detection and by the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), so if this is dark matter, we're already learning about its interactions from the lack of detection so far," said co-author Tracy Slatyer, a theoretical physicist at MIT in Cambridge, Mass. "This is a very exciting signal, and while the case is not yet closed, in the future we might well look back and say this was where we saw dark matter annihilation for the first time."

The researchers caution that it will take multiple sightings – in other astronomical objects, the LHC or in some of the direct-detection experiments now being conducted around the world -- to validate their dark matter interpretation.

"Our case is very much a process-of-elimination argument. We made a list, scratched off things that didn't work, and ended up with dark matter," said co-author Douglas Finkbeiner, a professor of astronomy and physics at the CfA, also in Cambridge.

"This study is an example of innovative techniques applied to Fermi data by the science community," said Peter Michelson, a professor of physics at Stanford University in California and the LAT principal investigator. "The Fermi LAT Collaboration continues to examine the extraordinarily complex central region of the galaxy, but until this study is complete we can neither confirm nor refute this interesting analysis."

While the great amount of dark matter expected at the galactic center should produce a strong signal, competition from many other gamma-ray sources complicates any case for a detection. But turning the problem on its head provides another way to attack it. Instead of looking at the largest nearby collection of dark matter, look where the signal has fewer challenges.

Dwarf galaxies orbiting the Milky Way lack other types of gamma-ray emitters and contain large amounts of dark matter for their size – in fact, they're the most dark-matter-dominated sources known. But there's a tradeoff. Because they lie much farther away and contain much less total dark matter than the center of the Milky Way, dwarf galaxies produce a much weaker signal and require many years of observations to establish a secure detection.

For the past four years, the LAT team has been searching dwarf galaxies for hints of dark matter. The published results of these studies have set stringent limits on the mass ranges and interaction rates for many proposed WIMPs, even eliminating some models. In the study's most recent results, published in Physical Review D on Feb. 11, the Fermi team took note of a small but provocative gamma-ray excess.

"There's about a one-in-12 chance that what we're seeing in the dwarf galaxies is not even a signal at all, just a fluctuation in the gamma-ray background," explained Elliott Bloom, a member of the LAT Collaboration at the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology, jointly located at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University. If it's real, the signal should grow stronger as Fermi acquires additional years of observations and as wide-field astronomical surveys discover new dwarfs. "If we ultimately see a significant signal," he added, "it could be a very strong confirmation of the dark matter signal claimed in the galactic center."

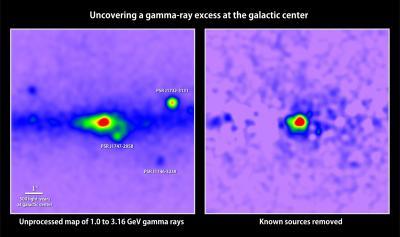

This animation zooms into an image of the Milky Way, shown in visible light, and superimposes a gamma-ray map of the galactic center from NASA's Fermi. Raw data transitions to a view with all known sources removed, revealing a gamma-ray excess hinting at the presence of dark matter.Various Broadcast quality formats: http://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/vis/a010000/a011500/a011513/

(Photo Credit: NASA Goddard; A. Mellinger, CMU; T. Linden, Univ. of Chicago)

At left is a map of gamma rays with energies between 1 and 3.16 GeV detected in the galactic center by Fermi's LAT; red indicates the greatest number. Prominent pulsars are labeled. Removing all known gamma-ray sources (right) reveals excess emission that may arise from dark matter annihilations.

(Photo Credit: T. Linden, Univ. of Chicago)

Source: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center